The Early Years of Rail

Pre-locomotive rail 18th Century

Before this period, horse-drawn wagons or carts had been used to transport goods. However, during the late 1700s, their wooden tracks were replaced with stronger iron ones. Horses were still the pulling power, but this would not be the case for much longer, as an innovation was on the horizon.

Steam power’s first appearance 1804

A bet between two industrialists in Wales led to the first successful steam-powered locomotive journey in history. Richard Trevithick, a Cornish engineer, designed the Pen-y-Darren locomotive that would step up to the task. In four hours, it successfully hauled 10 tonnes of coal for 10 miles, winning the bet and changing rail forever.

Paying passengers take to the rails 1807

Opened in 1806, the Mumbles railway was designed to make transporting cargo from quarries to markets easier. The next year, one of the railway’s shareholders suggested that some vehicles transported people instead of cargo. On 25th March 1807, the first paying passengers rode the horse-powered railway, paying two shillings to do so.

Trevithick showcases steam 1808

Richard Trevithick sought to win investment to push steam locomotives to the forefront of rail travel. To do so, he ran the first passenger fare-paying steam locomotive around a circular track in London. “Catch Me Who Can” did not convince investors, but Trevithick did prove that a steam locomotive could run on iron rails.

Passenger Locomotive Travel Begins

The world’s first steam-powered passenger railway 1825

On 27th September 1825, the Stockton and Darlington railway opened. This was the first railway that carried passengers using steam-powered locomotives, so it attracted a lot of interest. People, even news reporters, travelled from all across the country to get a glimpse of the train as it made its way along the 25-mile route. A holiday was even declared in Darlington to mark the occasion.

Stephenson’s Rocket 1829

The Rainhill trials of 1829 had one goal: to find the best mode of transport for the Liverpool and Manchester railway. Stephenson’s Rocket was the only locomotive to succeed in completing all trials, proving that steam was the best method of pulling trains. Soon, the Rocket’s technology was applied across the whole railway network, shaping the railways for years to come.

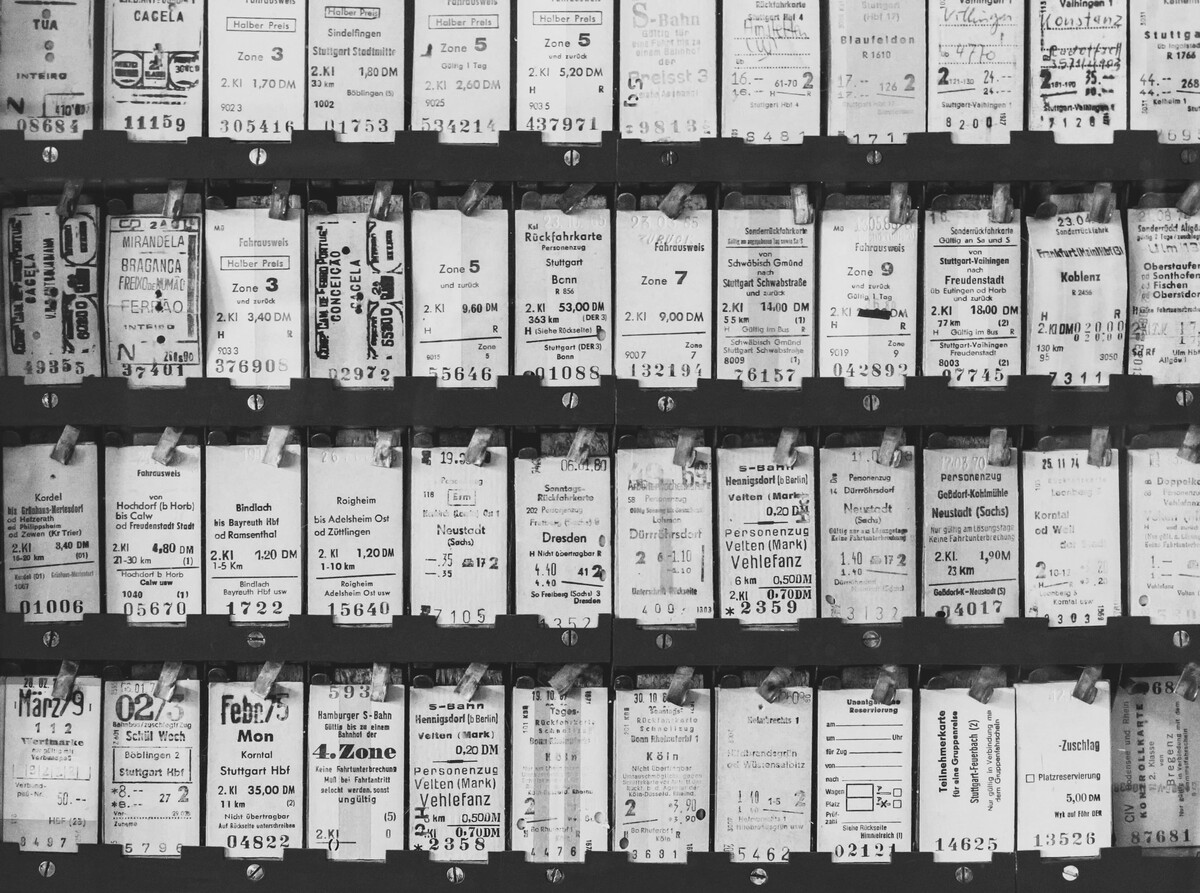

Edmondson tickets 1840s

With rail travel growing in popularity, the old method of writing train tickets by hand was no longer viable. In the 1840s, Thomas Edmondson introduced his system of pre-printed tickets. These tickets featured details of the journey passengers had paid for, including travel class. They also had a serial number to stop ticket clerks from pocketing the fares for themselves, which had become a growing problem.

Transporting royals 1841

A normal carriage would never suffice for royalty. Dowager Queen Adelaide, Queen Victoria’s aunt, toured Northern England in the first-ever royal carriage. The converted first-class carriage featured specially re-designed seats to accommodate her needs. Trains transported royals across the country for the next century, getting bigger and grander as time went on.

Third-class travel is upgraded 1844

Once passenger rail was up and running, trains established first and third class. First-class travel was more expensive, but this was reflected in the quality of the carriages and, initially, the fact that they had roofs. The Railway Regulations Act of 1844 changed this. Now, railway companies were required to have roofs on third-class carriages to protect passengers from the elements.

Railways’ Influence on Culture

Railways as an investment opportunity 1840s

As rail travel began to grow in popularity, and networks expanded, people wanted a slice of it. Investors big and small, as well as business owners, put a lot of money into the railways. From 1843 to 1845, Railway Mania, a stock market bubble in the rail transportation industry in the UK, saw thousands of rail lines proposed and the price of railway shares doubled. Sadly, share prices quickly fell and railways were overexpanded, leading to an overall downturn in the industry.

Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway 1844

In 1844, renowned artist J.M.W. Turner painted ‘Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway’ of a train in the countryside heading in the direction of the observer. It’s a dynamic image that blends the nature that everyone knew with the modern, industrial image of a speeding train. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Turner wasn’t averse to showcasing industry and technology in his artwork.

A world-first in law 1845

As rail continued to develop, so did other technologies. Telegraphy is one such example and became part of rail history in 1845 when John Tawell boarded a train in an attempt to flee a murder scene. Unfortunately for John, a telegraph had been sent ahead to a train station along the route, and railway police were able to catch him. This was the first ever arrest made using technology.

“Railway time” 1847

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) became the standard time for railways in Britain in December 1847, which had previously run on their own local time. This was a move to help reduce the risk of accidents and improve punctuality on the vast rail network. Soon, towns and cities adjusted their time to GMT too. By 1855, almost the whole of England and Wales were running on this so-called “railway time”.

Improving Services and Safety

Connecting Ireland 1852

The final rail link between Dublin and Belfast was completed by engineers in 1852. It is still the only railway line that crosses the border between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Despite the difficulties and conflicts during the 1800s, the railway continued to operate as normal. Even today, it is considered a vital line of communication between the two nations that make up the island.

Holiday travel 1860s

Rail ushered in the idea of mass tourism. In the 1860s, trains took tens of thousands of visitors to see the sea in Blackpool. Starting in the 1800s, workers took their holidays in the summer during the period when factories were shut down for maintenance. Different areas had different dates, but these shutdowns became known as Wakes Weeks or Fairs Fortnights (in Scotland).

Mail order 1861

It was the railways that saw the start of home delivery shopping. Pryce Pryce-Jones, a Welsh businessman and politician, decided to take advantage of the rail network and low postage costs. His idea was to send products to customers that they had chosen from catalogues using the trains. It was a resounding success, reaching the very top of society with Queen Victoria and other famous people like Florence Nightingale.

The London Underground 1863

London is home to the world’s first underground railway system. It opened in 1863 and used steam trains to connect passengers between 4 major overground stations. It took a while for it to really get going. In fact, it wasn’t until the early 1900s that the core of the Underground we know today was established. Today, the Underground remains a globally recognised symbol of London.

Sleeping becomes comfortable 1870s

Since railways moved so slowly initially, it wasn’t uncommon for people to sleep on them. In 1873, a sleeping service began on the East Coast Main Line. Operated by North British Railway, it featured seats that flattened to become a bed. Special sleeping carriages were built in the 1880s, making rail services more appealing and glamorous to passengers.

Improvements in signalling 1876

Train engineers could control many things, but sadly the weather was not one of them. In 1876, heavy snow got into the signal arm at Abbots Ripton, giving the impression that all was clear ahead. This, however, was not the case, and 13 people were killed in a crash that also wrecked three trains. In response, “danger” is made the default signal setting so that drivers do not presume the line ahead is all clear.

Innovating the Train Experience

Restaurant cars 1879

The first dining cars in Britain started serving food onboard Great Northern Railway services. Passengers enjoyed a six-course menu on the Prince of Wales dining car from Leeds to London King’s Cross, often featuring fashionable British or French recipes. Certain medical authorities expressed their concerns that eating quickly aboard a moving train would cause fatal indigestion. Thankfully, this did not happen, and dining cars became very popular.

“Shunter’s pole” 1886

Up until this point, vehicles had to be coupled together by a person standing somewhat precariously between them. In 1886, Mr. Tuff from York created a long, hooked pole that meant this job could be done from a safe distance. It was a humble invention, but responsible for saving thousands of lives. Tuff expressed his desire to not patent his invention so that it would spread more quickly and save as many people as possible.

The Forth Bridge 1890

The first major steel construction in Britain, The Forth Bridge was also the longest cantilever bridge in the world until 1919. It was built specifically for the railway line to go across the Firth of Forth, which is located to the west of Edinburgh. To mark the occasion, special bronze medals were created. The bridge is of such importance that it has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Standardisation, Unionisation, and Electrification

Nationwide adoption of standard gauge 1892

Up until this point, trains either operated on broad gauge or standard gauge. However, as trains started to travel on other companies’ rail lines, this became more of an inconvenience. In 1892, the final broad gauge train left Paddington station. Amongst the pageantry, thousands of railway workers were waiting along the route to swap the track over as soon as the train had passed. In just one weekend, Britain’s mainline railways were finally connected in one standard gauge.

Commuter trains powered electronically 1900s

The suburbs offered pleasant housing and green spaces, so quickly became popular. As people started to make their homes away from cities, they suddenly needed a way to still get into their places of work. Electric mainline trains were ideal as all they needed to do was stop, start, and then stop again when they got to the next station. These trains had a particularly big impact on London’s development and saw new suburbs being created.

National Union of Railwaymen 1913

Working on the railways could be very dangerous. Smaller local unions were already operating, and some of these merged to form the National Union of Railwaymen. Their goal was to come together and advocate for hundreds of thousands of railway workers. They did so by lobbying employers and running sickness and support groups. They also raised money for children of railway workers who had been injured or killed whilst working on the network.

Rail During the World Wars

The First World War 1914 - 1918

When war was declared between Britain and Germany, the rail networks became heavily relied upon. They were used to transport vast numbers of troops and equipment from the Home Front to France. Trains were also used to distribute rations, coal, and water across Britain and Europe to keep people alive as well as they could be in these times. More than 100,000 British railway workers enlisted in World War One and, tragically, over 20,000 never came home.

Women railway workers 1914 - 1918

Before the war, women were mostly employed in “appropriate” domestic-style roles on the railways. However, with the gaps left by men off fighting in the war, they began taking on clerical work and ticket collection. Eventually, they were also given roles as engine cleaners and station porters. While subject to severe discrimination, there were so many women now working on the railways that they were permitted to join unions in 1915.

Kindertransport 1938

As the Nazi regime was growing in power, Jewish child migrants escaped and were met on the platform at Harwich station. Mostly from Czechoslovakia (now Czechia), their parents had been forced to remain in their homeland whilst they were taken away to protect them. Over time, more and more Jewish children came to the safety of Britain across the channel via railway ferries. Sadly, many of them would never see their parents again.

World War Two 1939 - 1945

When Britain declared war on Germany for a second time, the railways were put to use once again. They were used to evacuate children from the cities to the countryside and move essential goods around the country. They were also sent to pick up some of the 338,000 troops who had been rescued from Dunkirk. However, this time, they were also a prime target. Railways suffered immense bomb damage as the enemy recognised how important they were to the war effort.

Women to the rescue 1939 - 1945

Unlike the First World War, women were actively recruited to help on the Home Front during World War Two, including on the railways. As a result of the national conscription of women, over 100,000 became part of the railway war effort. This time, there were fewer restrictions on the roles they could do, so some ended up filling roles like passenger guards and signallers. However, due to union opposition and the length of training required, women were still barred from becoming train drivers.

Nationalising Rail

The rise of nationalisation 1945 - 1946

After World War II, Britain’s railway network was in urgent need of repair, with war damage and financial strain leaving private operators struggling. The newly elected Labour government, led by Clement Attlee, saw nationalisation as the key to modernising public transport. Railways were viewed as essential infrastructure, too important to be left in private hands. This shift in political and public opinion paved the way for legislation that would bring the railways under state control.

The Transport Act 1947

The Transport Act 1947 laid the legal foundation for railway nationalisation in Britain. Passed by Clement Attlee’s Labour government, it transferred ownership of the ‘Big Four’ private railway companies, GWR, LMS, LNER, and SR, to state control. It also established the British Transport Commission (BTC), which would oversee rail, canals, and road haulage. This act marked a shift in how Britain’s transport infrastructure would be managed in the post-war era.

British Railways and the British Transport Commission 1948

The ‘Big Four’ railway companies officially merged into British Railways, creating a single, state-run network. This change aimed to standardise timetables, rolling stock, and operations. However, ageing infrastructure and financial struggles remained major challenges. To manage the nationalised transport system, the government set up the British Transport Commission. It oversaw railways, canals, road freight, and London’s public transport.

Japan National Railways 1949

Like Britain, Japan turned to railway nationalisation after World War II, creating Japan National Railways (JNR) in 1949. Over the years, it would rapidly expand urban commuter networks. It would also later introduce the world’s first high-speed service, the Shinkansen. Despite its early success, JNR faced mounting debts and operational inefficiencies. This would eventually lead to the government splitting it into private, regional companies.

The Dawn of Diesel

The Modernisation Plan 1955

In 1955, British Railways introduced a Modernisation Plan to revitalise the rail network amid growing road competition. The plan aimed to enhance speed, reliability, safety, and capacity by transitioning from steam to diesel and electric traction. This would be achieved through updating rolling stock and improving infrastructure. However, rushed diesel production led to reliability issues, and planners underestimated the rise of road transport. These challenges resulted in financial struggles and limited long-term success.

Introduction of diesel multiple units Late 1950s

To revive branch lines and suburban services, British Railways introduced diesel multiple units (DMUs) beginning in the late 1950s. Replacing steam-hauled trains on shorter routes, DMUs were cheaper to operate and easier to maintain. Their improved acceleration and quick turnaround times helped attract passengers back to rail in certain regions. They showcased diesel’s advantages over steam for local and commuter services.

Western Region experiments with diesel-hydraulics Late 1950s-1960s

In the late 1950s, British Rail’s Western Region experimented with diesel-hydraulic locomotives, inspired by Germany’s V200 class. This was when the rest of Britain was embracing diesel-electric traction. The ‘Warship’ (Class 42) arrived in 1958, followed by the larger ‘Western’ (Class 52) in the early 1960s. While these locomotives had strong power-to-weight ratios, they required specialised maintenance and didn’t fit British Rail’s standardisation plans.

The end of steam 1968

On 11 August 1968, British Rail ran its last scheduled mainline steam service, officially ending steam traction on the national network. The ‘Fifteen Guinea Special’ from Liverpool to Carlisle marked the occasion, drawing crowds of enthusiasts. While heritage railways would preserve steam for future generations, this moment cemented diesel as the backbone of British rail. The transition paved the way for further modernisation, leading to advancements in rail technology in the decades that followed.

Rails' Influence on Entertainment

The Railway Children 1970

The 1970 adaptation of The Railway Children brought E. Nesbit’s classic novel to life, just as Britain was moving away from steam. Filmed on the Keighley and Worth Valley Railway, it showcased the charm of rural stations and vintage locomotives. Jenny Agutter’s performance and the film’s nostalgic tone made it an enduring favourite. Its success reflected our lasting affection for rail travel, even as modernisation took hold.

Murder on the Orient Express 1974

The 1974 adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express brought Agatha Christie’s famous mystery to the big screen with an all-star cast. The film cemented the Orient Express as a setting for mystery and adventure, bringing train travel into the spotlight. Its success showed how railways could add drama and atmosphere to storytelling. While Britain’s rail network was becoming more modern and practical, the film reminded audiences of the magic of long-distance train journeys.

Silver Streak 1976

The thriller-comedy Silver Streak, starring Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor, turned a cross-country train ride into a high-speed mix of action and comedy. Its runaway train sequences and onboard chaos reinforced the excitement and drama rail travel could bring to film. Filming primarily took place in Canada, with the climactic train crash scene shot at Toronto's Union Station.

The First Great Train Robbery 1979

Starring Sean Connery and Donald Sutherland, The First Great Train Robbery dramatises an 1855 gold heist from a moving train. Connery performed his own stunts, including running atop a speeding train clocked at over 55 mph. This was faster than initially intended. Filmed primarily in Ireland, the production faced challenges such as insufficient steam locomotive power, leading to the discreet use of a diesel engine for assistance.

Major Shifts in the World of Rail

Advanced Passenger Train Trials 1979

In the late 1970s, British Rail embarked on the Advanced Passenger Train (APT) project. Its goal was to develop tilting trains capable of higher speeds on existing curved tracks. Its success led to the APT setting a UK speed record of 162.2 mph in December 1979. However, technical issues and negative press coverage led to its withdrawal from service by 1986. Despite its challenges, the APT's pioneering technology influenced future high-speed trains, including our Pendolino trains.

France launches TGV high-speed rail 1981

In 1981, France launched the Train à Grande Vitesse (TGV) service between Paris and Lyon. This marked Europe's first high-speed rail line, with it operating at speeds up to 168 mph and greatly reducing the travel time between the two cities. This introduction of high-speed rail demonstrated the potential for rapid transit and influenced others, including the UK, to consider something similar.

Sectorisation of British Rail 1982

In the early 1980s, British Rail restructured its operations into distinct business sectors to improve efficiency and financial stability. New divisions like InterCity, Network SouthEast, and Regional Railways were given clearer responsibilities and greater accountability. This sectorisation approach introduced more market-driven strategies, streamlining services and enhancing branding. While still under state ownership, the changes laid the groundwork for future privatisation.

The Railways Act of 1993 1993

The Railways Act 1993 marked the beginning of British Rail’s privatisation, bringing an end to full state control. Passenger services were gradually franchised to private operators, while rail infrastructure was handed to Railtrack, later replaced by Network Rail. It changed how services were run, timetables were set, and trains were procured. It also introduced competition, paving the way for new operators.

Opening of the Channel Tunnel 1994

In May 1994, the Channel Tunnel opened, creating the first direct rail link between the UK and mainland Europe. The 31-mile undersea tunnel connected Kent with northern France, a major feat of engineering. Eurostar services soon followed, cutting journey times to Paris and Brussels and transforming cross-border travel. In 2003, a Eurostar train set a new British speed record of 208 mph on the first section of High Speed 1, the railway linking London and the Channel Tunnel.

The Start of Modern Rail

West Coast Modernisation 1998

The West Coast Main Line (WCML), one of Britain’s busiest intercity corridors, underwent an extensive, decade-long upgrade. The upgrade introduced new tracks, station improvements, and advanced signalling to support 125 mph services. Despite delays and rising costs, the project significantly improved journey times and reliability. It laid the groundwork for faster, more efficient rail travel, paving the way for high-speed services.

Pendolino trains arrive at the West Coast 2002

In 2002, Class 390 Pendolino trains entered service on the West Coast Main Line, bringing faster and smoother journeys. Their tilting technology, inspired by the APT experiments, allowed them to take curves at higher speeds without major track upgrades. With their streamlined design and rapid acceleration, they marked a shift toward modern, high-speed electric travel.

Railtrack becomes Network Rail 2002

Railtrack plc was created in 1994 to manage rail infrastructure under the newly privatised system. However, financial troubles and criticism following several high-profile accidents led to its collapse. In 2002, the not-for-dividend company Network Rail assumed Railtrack’s responsibilities. This shift marked a crucial step in re-establishing more direct state oversight of infrastructure in Britain’s railways.

The contactless era begins 2003

Launched in 2003, the Oyster card revolutionised travel across London’s transport network. Originally for the Underground and buses, it soon expanded to National Rail services within the capital, making fare payment faster and more convenient. The system reduced queues and streamlined ticketing, marking a major step toward digital integration.

St Pancras and High Speed 1 2007

Reopened in November 2007, St Pancras International became the new home of Eurostar as the final phase of High Speed 1 was completed. The redevelopment combined Victorian architecture with modern engineering, creating a world-class high-speed rail hub. Faster journey times to Europe reinforced rail’s role in international travel, while St Pancras’ transformation highlighted the benefits of major infrastructure investment.

Modern Milestones

The Great Western Main Line upgrade 2012

Launched in 2012, the Great Western Main Line upgrade aimed to modernise key routes from London Paddington to South Wales and the West. The upgrade introduced faster, more efficient electric trains, reducing journey times and cutting emissions. Despite delays and rising costs, it paved the way for new Hitachi-built Class 800/801 trains, blending electric and diesel power for greater flexibility. The project marked a major step toward a cleaner, high-capacity rail network.

The London Bridge Redevelopment 2013

Dating back to the 1830s, London Bridge is the city’s oldest terminus station. Between 2013 and 2018, it underwent a £1 billion transformation, improving capacity, passenger facilities, and Thameslink connections. The redevelopment introduced longer platforms, a spacious concourse, and better accessibility, easing congestion for millions of travellers.

The return of The Flying Scotsman 2016

Following a decade-long, multi-million-pound restoration, the legendary Flying Scotsman returned to mainline service in February 2016. As one of Britain’s most famous steam locomotives, its revival captivated rail enthusiasts and the wider public alike. As the first steam engine to reach 100 mph and a symbol of Britain’s engineering, its revival was a landmark moment for rail preservation

The Restoring Your Railway fund 2020

Launched in January 2020, the “Restoring Your Railway” fund committed £500 million to reviving rail links lost in the Beeching cuts of the 1960s, a period of significant cutbacks and closures. Key projects include the Northumberland Line, set to reconnect Ashington with Newcastle, and feasibility studies for reopening other disused routes. As more communities regain rail access, the programme signals a long-term investment in regional connectivity.

Launching the Evero Fleet 2024

Our new Evero fleet was introduced in June 2024 and will replace our Voyagers. Built by Hitachi, the 23-strong fleet, consisting of 10 seven-carriage electric trains and 13 five-carriage bi-modes, will serve routes from London to the Midlands, Chester, North Wales and the North West, leading to a substantial cut in carbon emissions with an increase in seats, and offering improved comfort. Quieter and roomier, with more reliable Wi-Fi, wireless charging for electrical devices and a real-time customer information system, these new trains are the result of a £350m investment in sustainable travel.

Welcoming the Future of Rail

Digital signalling and the European Train Control System 2025

Network Rail's "Digital Railway" strategy aims to replace traditional signals with in-cab systems like the European Train Control System (ETCS). This technology allows trains to run closer together safely, boosting capacity and reducing delays. The Cambrian Line in Wales was the first in Britain to implement ETCS in 2011. Future rollouts are planned for major routes, including the East Coast Main Line, in 2025.

HS2 2029

HS2 is the largest rail infrastructure project in modern British history. It is designed to improve capacity and cut journey times between London, Birmingham, and eventually Manchester. The first phase linking London to Birmingham started in 2017 and is expected to open between 2029 and 2033. Despite cost debates and route changes, HS2 is set to deliver faster intercity travel and boost the economy in the Midlands and North.

Hydrogen and battery-electric trains 2030

The push for greener rail travel is driving the development of hydrogen and battery-electric trains. In 2024, a UK trial saw a battery-powered train reach speeds over 75 mph, covering up to 43 miles on a single charge. Meanwhile, trains like HydroFLEX are in testing, with the UK targeting wider adoption by 2030. These trains could replace diesel on non-electric routes and help the UK reach net zero.

Celebrate 200 years of rail in 2025 with Avanti

2025 will see the country celebrating 200 years of rail history. Learn more about Railway 200 with Avanti, as we explore train culture, information about train performance, and the history of the UK’s railways.

- The Early Years of Rail

- Passenger Locomotive Travel Begins

- Railways’ Influence on Culture

- Improving Services and Safety

- Innovating the Train Experience

- Standardisation, Unionisation, and Electrification

- Rail During the World Wars

- Nationalising Rail

- The Dawn of Diesel

- Rails' Influence on Entertainment

- Major Shifts in the World of Rail

- The Start of Modern Rail

- Modern Milestones

- Welcoming the Future of Rail